The Battle of Bothwell Bridge

Overview

“The Battle of Bothwell Bridge” appeared in the Minstrelsy from the 2nd edition in 1803, and appears in all subsequent editions covered by this project. It is the 66th ballad in the 1803 edition. Scott states that he gained the ballad from recitation.

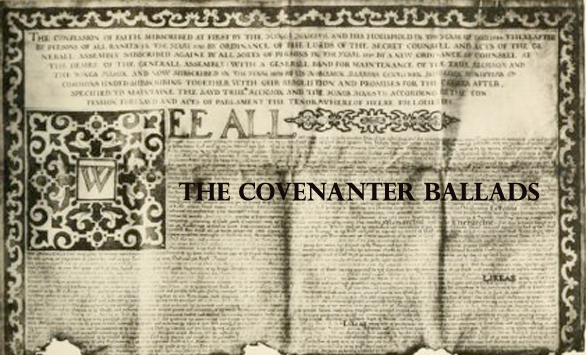

“The Battle of Bothwell Bridge” is concerned with one of the military events which reflect the religious and political struggles during the reign of Charles II, whom the Covenanters believed had reneged on promises he had made to them, and indeed his signing of the Covenant. The ballad is pro-Covenanter, and this must be considered when reading it. There is also extreme contraction of time in the final verses, and no little amount of manipulation of the facts.

History

The Battle of Bothwell Bridge took place over several hours on 22nd June 1679, which fell on a Sunday. There were around 4000 men in the Covenanting force, led by Sir Robert Hamilton, against a force of around 5000, led by the Duke of Monmouth (Charles II’s eldest illegitimate son). Around 300 Covenanters, realising the strategic importance of the bridge, held it against the Royalist troops, with only one cannon for heavy artillery. Despite sending requests for support, they ran out of ammunition and reinforcements from Hamilton Moor – where the Covenanters were camped – never materialised.

The desperate defenders were forced to surrender the bridge and retreat under a mounted dragoon attack, and join the main body of their force on the moor, but there, concern spread through many of the men that they had been deserted by their officers, which affected morale and the structure of the force.

Engaging the enemy, the Covenanting cavalry charged the Royalist forces, but were forced back into their own infantry. The infantry lines then broke. All order was destroyed within the Covenanting force, and many fled. The battle which began with a resolute stand-off on the bridge ended in a rout.

Claverhouse was second in command at Bothwell Bridge and took a vicious revenge for Drumclog. Around 400 Covenanting troops died in the rout, but around 1200 were taken prisoner. These men were force-marched to Edinburgh, where they were imprisoned in the grounds of Greyfriars’ Kirk, ironically, the place where the first Covenant had been signed in 1638. Instead of being a place of inspiration for the Covenanters, it became their prison, and very often where they died, held as they were in all weathers with no shelter. Actions like this gained Claverhouse the epithet “Bluidy Clavers”.

Hamilton's reasons for not offering support to the defenders o the bridge may be that there was simply no ammunition and men spare. However, neither did he offer any resistance to the Government troops when they crossed the bridge and reformed their lines: it may have been incompetence, or it may have been that the factions which always existed within the Covenanting force – some who still insisted on Godliness above military aplomb – and made it impossible to create an effective, operating army. Scott himself supposes that this could have been the issue

Information regarding the site and the battle can be found on the Battlefields Trust site, in Historic Scotland’s site information and on Canmore.

Characters

There are several individual characters named in the ballad.

- Earlstoun – Alexander Gordon of Earlstoun (1650–1726)

This character represents Alexander Gordon of Earlston, who was a prominent covenanter. His father was killed on his way to assist in the fighting at Bothwell Bridge. Alexander himself escaped with his life after the battle – thanks, it is said, to one of his servants, who dressed him in women's clothing and set him to rock a cradle while the Government tropps searched for him.

He was declared outlaw and his estates taken and sold. He lived for a while in exile in Holland, but in 1683, having travelled to Newcastle after a visit to Edinburgh, about to return to Holland to promote covenanter causes, he was arrested on board ship and returned to Edinburgh. Instead of being executed, he was to be tortured on the king’s orders. His violent response to this won him the name the Bull of Earlston. He was then imprisoned at Blackness until 1689. After help from his family, he returned to Earlstoun and remained there until his death. - Monmouth – James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, 1st Duke of Buccleugh (1649-1885)

James Scott (formerly Fitzroy or Crofts) was the eldest illegitimate son of Charles II and his mistress Lucy Walter. He took his wife’s surname when they married. He was given control of the government force against the covenanting army and was in command at Bothwell Bridge, although he was removed from this post a day later, on orders, and replaced by General Tam Dalziel. Prior to the battle, he had tried to agree terms with the more moderate faction of the Covenanters, but the terms were still being debated by the Covenanter officers when the Government troops first made an approach on the bridge.Monmouth was executed in 1685, after his attempt to wrest power from his uncle James VII, not as the ballad would portray it, due to Claverhouse's intervention. - Claverhouse – John Graham of Claverhouse, 1st Viscount of Dundee (c.1648–1689)

Claverhouse was a staunch supporter of the royalist cause, although he did not let religious causes interfere with other aspects of his life: he married Jean Cochrane of a staunchly covenanting family.

While Graham of Claverhouse may have been known as “Bonnie Dundee” to the Government faction, to the Covenanters, he was known as “Bluidy Clavers” and, along with General Tam Dalziel, Claverhouse was among the most hated and reviled members of the Government forces. The mythology surrounding him, from the Covenanting faction, afforded him some kind of supernatural status: it was said that he cold only be killed by a silver bullet.

He led the royalist troops at Killiecrankie and while the royalists won the battle, Dundee was shot and died of his wound later in the day. He is buried in St bride’s Kirk near Blair Castle.