Fair Helen of Kirconnell

“Fair Helen of Kirconnell” was included in the Minstrelsy of the Scottish Borer from the first edition of 1802, where it was published in the first volume. Scott's noted that the Minstrelsy version of the ballad “is here given, without alteration or improvement, from the most accurate copy which could be recovered”. There is a version of this ballad in the Glenriddell MS, but Scott's does deviate from it in vocabulary and stanza order. However, Scott woul dhave known about it.

Although he presents two parts of the ballad, Scott recorded his own suspicions regarding the first part – “ the Editor cannot help suspecting, that these verses have been the production of a different and inferior bard, and only adapted to the original measure and tune. But this suspicion being unwarranted by any copy he has been able to procure, he does not venture to do more than intimate his own opinion” (MSB (1802): I 73). It should be noted that while this ballad is still popular among singers, the first part has all but fallen out of use. This may be due to the style of the language, but it is more likely that it has to do with it not being compatible with traditional ballad structures and language.

History & Tradition

While Scott states that the “affecting incident on which is it founded, is well known”, he then admits that there is some confusion over such details as the heroine’s surname (Irvine or Bell), and while the location is not in dispute within the traditions surrounding the events of the ballad, the surname “depends upon the period at which she lived, which it is now impossible to ascertain”. The tradition surrounding this ballad reads more like hearsay. It does not involve a national incident, but a domestic murder, which does not detract from the impact of the piece. One of the earliest accounts of the anecdotal history surrounding this ballad was presented in the 1772 publication, A Tour in Scotland and Voyage to the Hebrides by Thomas Pennant. Pennant notes the site of two graves, and recounts the tale of Helen Irvine and Adam Fleming. His account follows the tale of the ballad very closely.

While Scott states that the “affecting incident on which is it founded, is well known”, he then admits that there is some confusion over such details as the heroine’s surname (Irvine or Bell), and while the location is not in dispute within the traditions surrounding the events of the ballad, the surname “depends upon the period at which she lived, which it is now impossible to ascertain”. The tradition surrounding this ballad reads more like hearsay. It does not involve a national incident, but a domestic murder, which does not detract from the impact of the piece. One of the earliest accounts of the anecdotal history surrounding this ballad was presented in the 1772 publication, A Tour in Scotland and Voyage to the Hebrides by Thomas Pennant. Pennant notes the site of two graves, and recounts the tale of Helen Irvine and Adam Fleming. His account follows the tale of the ballad very closely.

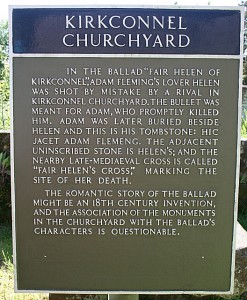

In the burying-ground of Kirkonnel is the grave of fair Ellen Irvine, and that of her lover: she was daughter of Kirkonnel; and was beloved by two gentlemen at the same time; the one vowed to sacrifice the successful rival to his resentment; and watched an opportunity while the happy pair were sitting on the banks of the Kirtle, that washes these grounds. Ellen perceived the desperate lover on the opposite side, and fondly thinking to save her favorite, interposed; and receiving the wound intended for her beloved, fell and expired in his arms. He instantly revenged her death; and then fled to Spain, and served for some time against the infidels; on his return he visited the grave if his unfortunate mistress, stretched himself on it, and expiring on the spot, was interred by her side. A sword and a cross are engraven on the tomb-stone, with hic jacet Adam Fleming: the only memorial of this unhappy gentleman, except an ancient ballad of no great merit, which records the tragical event. (Pennant (1776) i: 101)

This seems to be one of the earliest references connecting this ballad to an event, but the ballad and the tradition seem inextricably linked.

Scott’s version is a little more detailed: he notes that the murdered carried a carbine and that Helen was shot as she tried to protect her lover from the gunfire. Scott also admits to the debate surrounding Fleming’s response. One account says that the two men fought there and then and Fleming killed the other man, while the other account suggest sthat the killer was pursued as far as Spain and was killed in the streets of Madrid. There is yet another account, not mentioned by Scott, which suggests that Fleming fled and spent years on the Continent, while at home he was eventually cleared of what looked like a double murder. He then, as in the Pennant account, returned to Kirkconnell and died at Helen’s grave.

Locations

There are gravestones which are said to be those of Helen and Fleming. There is also a cross, called “Fair Helen’s Cross”, which is said to mark the spot where she died. However, there are several points to be noted: inscriptions can be added to extant ancient gravestones, and objects can be moved. For example, the Grand Tour, an expected event within any educated young man of means’ life, came to a sudden end with the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. At one point, travel to those parts of Europe necessary for a “proper” Grand Tour was all but impossible. People turned their eyes towards their own countries. Places linked to popular traditions were located and exploited: for example, in Beddgelert, Wales, the “burial mound” of the faithful hound Gelert was created in the 18th century by David Prichard, landlord of the nearby Goat Hotel, with an eye on the developing tourist trade. Notes made by archaeologists regarding Fair Helen’s Cross suggest that it may well have been moved to the spot where it now stands.vYou can view more information about the gravestones here

There are gravestones which are said to be those of Helen and Fleming. There is also a cross, called “Fair Helen’s Cross”, which is said to mark the spot where she died. However, there are several points to be noted: inscriptions can be added to extant ancient gravestones, and objects can be moved. For example, the Grand Tour, an expected event within any educated young man of means’ life, came to a sudden end with the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. At one point, travel to those parts of Europe necessary for a “proper” Grand Tour was all but impossible. People turned their eyes towards their own countries. Places linked to popular traditions were located and exploited: for example, in Beddgelert, Wales, the “burial mound” of the faithful hound Gelert was created in the 18th century by David Prichard, landlord of the nearby Goat Hotel, with an eye on the developing tourist trade. Notes made by archaeologists regarding Fair Helen’s Cross suggest that it may well have been moved to the spot where it now stands.vYou can view more information about the gravestones here

There are other ballads, such as “Mary Hamilton”, entitled “Lament of the Queen’s Marie” in the Minstrelsy, or “The Gypsy Laddies”, which have had various historical events assigned to them. These tend to be those ballads which have numerous variants, and which seem to contain evidence to connect the ballad to several events. The evidence connecting “Fair Helen of Kirconnell”, to any one historical event is, however, extremely slim. However, it would be churlish not to acknowledge that in the anecdotal history connecting the ballad to the actual individuals buried in Kirkconnell graveyard, there may be at least some grain of historic origin.

The Two Parts of the Ballad

Neither part of “Fair Helen of Kiconnell” portray formulas or language typical of traditional ballads, and both include other aspects which sets the pieces apart. For example: both are presented entirely in the first person; the use of metaphoric language is not in any way common to the tradition; and the rhyme form aaab is atypical. Moralising language is not common in ballad versions, although some which have been popular both in print and the oral tradition, such as “Mill of Tifty’s Annie” may include moralising verses, such as that found in verse 2 of the first part of this ballad.

As the first part has fallen out of favour with singers, we have provided interpretative notes only to the second. However, it may prove interesting to contrast the two parts, and to this end, we have provided the stanzas to the first part here.

Fair Helen of Kirconnell Fair Helen – Part First O! Sweetest sweet, and fairest fair, Of birth and worth beyond compare, Thou art the causer of my care, Since first I loved thee. Yet God hath given to me a mind, The which to thee shall prove as kind, As any one that thou shalt find, Of high or low degree. The shallowest water makes maist din, The deadest pool the deepest linn, The richest man least truth within, Tho’ he preferred be. Yet nevertheless I am content, And never a whit my love repent, But think the time was a’ weel spent, Tho’ I disdained be. O! Helen sweet, and maist compleat, My captive spirit’s at thy feet, Thinks thou still fit thus for to treat Thy captive cruelly. O! Helen brave, but this I crave, Of thy poor slave some pity have, And do him save that’s near his grave, And dies for love of thee.

____________________________________

Image attributions:

Kirkconnell Graveyard –

© Copyright Anne Burgess and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

Notice in Kirkconnell Graveyard –

© Copyright Anne Burgess and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence