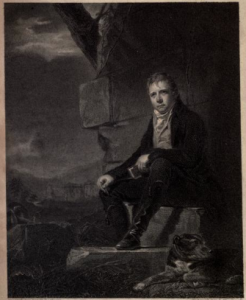

Walter Scott

Walter Scott

For a comprehensive timeline of Scott’s life, see the University of Edinburgh Walter Scott Digital Archive, specifically the chronology pages. The site also includes details about correspondence, the novels, Abbotsford and definitive collections.

Scott was 31 years old when the first edition of the Minstresly of the Scottish Border was published. A married man, with a wife and a young child to support, he was an advocate, based in Edinburgh, and had also recently attained the post of Sheriff Depute of Selkirkshire. However, he had been collecting ballads and songs for some years, and his love of the singing traditions, which he presented in the Minstrelsy, was much more than a brief flirtation with a sole eye on publishing success.

Scott was 31 years old when the first edition of the Minstresly of the Scottish Border was published. A married man, with a wife and a young child to support, he was an advocate, based in Edinburgh, and had also recently attained the post of Sheriff Depute of Selkirkshire. However, he had been collecting ballads and songs for some years, and his love of the singing traditions, which he presented in the Minstrelsy, was much more than a brief flirtation with a sole eye on publishing success.

Scott has often been viewed as a kind of literary interloper – a moneyed, Edinburgh man, who built himself a baronial palace in the Borders and played at living like a laird of old. He is often also viewed as a copyist and a faker – a man who did not present the material he collected “as is”, but who added, altered and edited great swathes away, to be lost for future generations. This is a simplified view, but it is something which hangs around Scott’s reputation somewhat like the Ancient Mariner’s albatross.

From a modern fieldworking point of view, what Scott did with the material was not good practice. However, he never intended to create an archive of variants of Scottish ballads or songs, and he was not the only individual, who collected songs or tunes and then edited them to a personal or publisher’s preference or agenda. He was passionate about collecting what he feared was a fading tradition, and what he did do with the Minstrelsy was to present a collection of ballads and songs for an eager literary audience, who may have lost touch with their own local singing traditions, or who were of a class who were not comfortable admitting that these songs and ballads were known and loved within their family. Like Bishop Percy’s Reliques of Ancient Poetry, Scott’s Minstrelsy permitted these ballads and songs – with their passions, delights, blood-thirsty revenges, defiance and despair – to be acceptable to a wider audience.

However, his connection with the ballads and songs was much more than as a collector once removed from the tradition. Like other Scottish poets and writers of the 18th and 19th centuries, he had a direct relation to the traditions he recorded in the Minstrelsy, and his feelings for the ballads, tales and the characters within, should not be viewed as being anything less than genuine.

There are several events in Scott’s life, which may have had some bearing on the collecting of ballads and songs, which led to the publication of the Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, and we have noted these key events, in order to show the strong family links Scott had with the Borders area, and to highlight the chance meetings and opportunities which occurred and which would help in the publication of the Minstrelsy.

Health

The young Walter Scott’s health was at times precarious. In The Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart, he recounts that he almost died “in consequence of my first nurse being ill of a consumption, a circumstance which she chose to conceal, though to do so was murder to both herself and me”. At the age of around 18 months, he contracted polio. Polio is a viral disease which is highly contagious, and while it has been all but eradicated in the UK since the introduction of a vaccine in 1955, it was endemic throughout Europe in the 19th century. The dark and unsanitary conditions in College Wynd, which lay off the Cowgate in Edinburgh, may have contributed to the disease being able to infect the little boy. Such conditions which were replicated throughout most of Edinburgh’s wynds and closes, and the consequent associated diseases were no respecters of rank or social position.

Contracting polio was to affect Walter Scott for the rest of his life. The disease left him lame in his right leg, and also restricted his movement in his early years. A great deal of his early life was spent away from his parents, recuperating or in seek of cures for his delicate health. His frequent companion and guardian was his father’s sister, Janet Scott – Scott’s Aunt Jenny.

His family hoped that spending time at his grandparents’ farm of Sandy-Knowe in the Borders would help cure the muscular damage done by the bout of polio. His grandmother and his Aunt Jenny entertained him with Border tales and songs – he noted in his autobiographical memoir, which prefaces the first volume of The Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart that “the old Border depredations were a matter of recent tradition” of his grandmother’s youth.

He was also told tales specific to the Scott family which related to 17th century Royalist-Parliamentary struggles, Covenanting times and the 1715 Jacobite Rising, and the young Walter was in direct contact with people who had witnessed some of the events he was told about, such as, Scott notes, a Mr Curle, who had witnessed the executions of Jacobites at Carlisle.

Recurrent bouts of ill health – and trips to places such as Bath for water cures – resulted in the young Walter spending little time with his parents in Edinburgh, with many months being spent in the Borders at Sandy Knowe and in Kelso. He notes himself that this was most probably extremely beneficial to his health – “I who in a city had probably been condemned to helpless and hopeless decreptitude, was now a healthy, high-spirited, and, my lameness apart, a sturdy child” (Memoirs 27) – but it most probably also was instrumental in maintaining and developing his interest in traditional songs and tales. If he had spent more time at his parental home at George Square, Edinburgh, he may not have had such license with his reading material. Living in Kelso with his aunt provided access to a treasure-trove of volumes, as Scott himself noted: a “respectable subscription library, a circulating library of ancient standing, and some private book-shelves, were open to my random perusal” (Memoirs 35). It was in Kelso that Scott “first became acquainted with Bishop Percy’s Reliques of Ancient Poetry”, and he subsequently gained access to Dr Blacklock’s library in Edinburgh, which gave the young Walter the opportunity to read the poem Ossian (later discovered to be a fake) and the works of Spenser. Such a range of reading, evidence indicates, would not have been tolerated in his parents’ home.

Education

Walter Scott’s education may seem rather erratic to many people today, but it is not entirely unrepresentative of the education impressed upon a boy of his social status. Scott’s education, however, was interrupted by bouts of ill health, which may have been related to the childhood polio attack.

Some of his formal education initially took place at the Grammar School, or High School of Edinburgh. The school did not offer arithmetic or writing as part of its curriculum, so his father engaged one James Mitchell as a tutor for these subjects. However, Mitchell, due to his religious background, also informed Scott, most probably on a much less formal basis, about Church history, including that of the Covenanting times. Scott, in his writings, presents himself as a rather reluctant pupil, saying “I did not make any great figure at the High School” (Memoirs 30) and “I made a brighter figure in the yards than in the class” (Memoirs 31).

Scott also attended the grammar school in Kelso, where is aunt lived. He spent four hours a day there. Some of his schoolfellows were James and John Ballantyne, who would go on to publish many of Scott’s works.

In 1783, aged 12, he attended Edinburgh University to study Classics. While attending university, he made friendships and acquaintances which would would prove influential in his professional life at the bar.

Scott left university, to begin an apprenticeship to the profession of Writer to the Signet. However, when it was decided that he should become a lawyer, he returned to university, initially attending classes in Moral Philosophy and Universal History before formally studying law.

Career

Scott qualified in 1792 and began practising as an advocate. He did not begin his professional life in Edinburgh, but worked on provincial circuits, notably Jedburgh. This was the year of the first “Liddesdale Raids”.

He married Charlotte Carpenter in 1797, and their first child, Sophia, was born in 1799. As husband and a father, Scott needed to procure a steady income and in December 1799, he gained the post of Sheriff-Depute of Selkirkshire – a post he retained until his death. This did not interfere with this advocate’s position, and it also meant that he could live in Erdinburgh for most of the year, but also retained a presence in Selkirkshire – perfect for his ballad collecting. However, by 1805, and with the imminent birth of his fourth child, Scott was doubting his chances of advancing in his career as an advocate. Seeking a salaried position, in 1806, he secured the appointment of Clerk of the Court of Session in Edinburgh, which assured financial stability for his family.

In 1802 the first edition of The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border was published by the Bannantyne Press in Kelso, to almost universal acclaim. Along with The Lay of the Last Minstrel, it assured Scott’s position as a literary writer of merit.

He continued to edit and expand the Minstrelsy over the years. The Minstrelsy endured, through Scott’s notorious financial crises of 1813 and 1825-6, and the period when he was writing in attempt to clear the debts which had accrued. What began as a debt of £121 000 in 1826, had been reduced to £53 000 at the time of Scott’s death in 1832 (the fifth edition of the Minstrelsy was published posthumously, although it was produced under Scott’s editorial control), and was finally cleared in 1847, after the sale of copyrights.